By Rathindra Kuruwita – Associate Fellow SAFN

5th June 2023

Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremesinghe visited Japan, almost immediately after the G7 meeting ended, in a bid to rebuild Sri Lanka’s relationship with Japan, which had soured in the last few years due to the sudden cancellation of projects, and to seek Japanese assistance in Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring.

There seem to be positive developments in both outcomes. In April, Japan announced that it along with India and France will organize a meeting of Sri Lanka’s creditor nations to promote the restructure of the country’s debt. China too will be invited, Japan said.

Meanwhile, the two countries seem to have ironed out the issues pertaining to the Light Rail Transit, Metro system in Colombo which was cancelled during the Gotabaya Rajapaksa regime. The LRT project was estimated at 1.5 billion US dollars, when it was proposed in 2017. The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) funded project was to be the largest single foreign-funded infrastructure project in Sri Lanka. The cancellation of the project soured Sri Lanka’s relations with Japan.

Ever since elected to power by Sri Lankan parliamentarians, Wickremesinghe has been trying to win Japanese investments and has introduced a rudimentary investment protection scheme.

During the president’s visit to Japan, Sri Lanka’s Cabinet spokesman Minister Bandula Gunawardene said they approved a proposal by President Ranil Wickremesinghe to seek parliamentary approval for agreements on foreign investment, adding that in the past leaders had stopped foreign investment projects according to their whims and fancies and such ad hoc decisions had cost the country dear. “The President left for Japan after obtaining Cabinet approval for measures to protect foreign investment. Such assurances are needed if we are to attract foreign investment,” he said. This was seen as a direct reference to the LRT project cancelled during the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration.

Following Wickremesinghe’s return to Sri Lanka, the Cabinet approved the recommencement of the LRT project, announcing the return of Japan as a key investor in Sri Lankan infrastructure.

G7 and South Asia

Wickremesinghe’s visit took place at a crucial juncture for the G7 nations and South Asia. While the recently concluded summit prioritized Russia’s ongoing conflict in Ukraine and China’s growing assertiveness in the Asia Pacific region, it was also an opportunity for the G7 member nations to demonstrate their capacity to assist and support to the developing world.

South Asian nations want the G7 countries to demonstrate that they really care for the international system – that the seven nations portray themselves to be guardians of – and address vulnerabilities that they are facing.

Economic vulnerability has surged in South Asia, accompanied by political tensions. While Sri Lanka and Pakistan are the poster children of South Asian economic crisis, the other countries too are under great economic strain and there is a belief that these issues are partially influenced by the actions of G7 countries. G7’s efforts to protect themselves from inflation by tightening liquidity and money supply have inadvertently triggered an international credit crunch, disproportionately affecting poorer nations. As the G7 faces its own economic challenges, there may be a temptation to downplay efforts to stabilize the finances of more fragile economies. However, this approach would be short-sighted, both from an economic and peace and security standpoint as it would drive the crisis ridden South Asian nations towards alternatives.

Long-term economic recovery of South Asian nations requires political stability, economic reform, and support from various international institutions in addition to IMF assistance. Creditors, including G7 countries, should consider strategies used in previous debt crises, such as debt restructuring with lower payments and extended repayment periods, as well as suspending obligations during good-faith negotiations. Creditors may also need to accept writing down the value of loans to alleviate the crisis, and fast.

In the past, the majority of sovereign debt was held by G7 countries, which collaborated through the Paris Club to contain crises. However, with China now being the world’s largest creditor and other players holding significant debt, a more inclusive debt relief approach is needed. The G20’s Common Framework and the subsequent Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable, involving private lenders, aim to address these challenges. G7 nations should encourage reconsideration of the IMF’s rigid approach to subsidy removal, which often sparks unrest, as in Sri Lanka and Pakistan, and explore alternative solutions. They could also assist countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Bangladesh in expanding unemployment insurance to mitigate the impact of inflation-curbing monetary policies.

In the case of Pakistan, the interlinked challenges it faces could destabilize the country further and increase conflict risks during an election year without a serious commitment from the developed world. Political polarization, a struggling economy, and recent protests highlight the fragile situation. The G7 states need to consider the potential for violence if fuel subsidies are removed amidst widespread suffering and a heated electoral campaign. They should leverage their influence with the IMF to advocate for favorable loan terms and more flexible short-term conditions, including targeted rather than generalized subsidies for fuel and electricity.

Overall, the G7 leaders must demonstrate a vision of leadership that goes beyond Western interests and addresses the vulnerabilities of South Asian nations. They should actively support debt relief efforts, explore alternatives to subsidy removal, and advocate for favorable loan terms to prevent further instability and promote global goodwill.

G7 and the perils of being India centric

India was invited to the rrecent G7 meeting, an indication of both India’s importance to the G7 nation as a key partner in Asia to counter China as well as a G7’s India First strategy with regards to South Asia.

In recent years, G7’s South Asia policy has primarily centered around India and is largely motivated by the goal of countering China’s regional and global influence. The G7 recognizes India as a key player in the region and a potential strategic partner in its efforts to address China’s growing presence. While Japan enjoys a positive relationship with most South Asian countries, it has followed the G7 blueprint and has made India the cornerstone of its South Asia policy.

However, Japan’s close association with India may raise concerns among other nations in the region. India’s sometimes overbearing approach and interference in the internal affairs of neighboring countries have been a source of irritation, which in turn may drive them closer to China. Consequently, any disputes that arise between India and its South Asian neighbors can create unease for Japan.

If South Asian countries view the Japan-India partnership as necessary to counter China’s influence in the region, particularly in light of the Quad’s reintegration, their reluctance to engage in such a partnership can have implications for bilateral relationships with Japan.

This was a point raised by President Wickremesinghe when he addressed the ‘Nikkei Forum: Future of Asia,’ in Tokyo on May 25. Referring to the principles outlined during the 1955 Asian African Conference in Bandung and the UN Declaration of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace, Wickremesinghe emphasized that Asian nations would avoid aligning themselves with any particular side in the global power competition.

“All of our countries benefited from the cooperation between the US and China in the post-Cold War era. Yet the subsequent rapid rise of China and the inability of the two countries to agree on China’s role on the international stage have led to rivalry and needless tensions in our part of the world. Thus the WTO system put in place three decades ago should not be by-passed for short term geo-strategic gains. The rules of the game cannot be changed arbitrarily. The losers will be the middle-income Asian countries,” President Wickremesinghe said.

Wickremesinghe’s sentiments are shared by most South Asian nations whose main concern is rebuilding and developing their own economies by benefitting from global trade. As Wickremesinghe noted, Japan who is looked up to by most South Asian nations can play a major role in ensuring that the region remains peaceful and countries are not forced to choose between two competing camps.

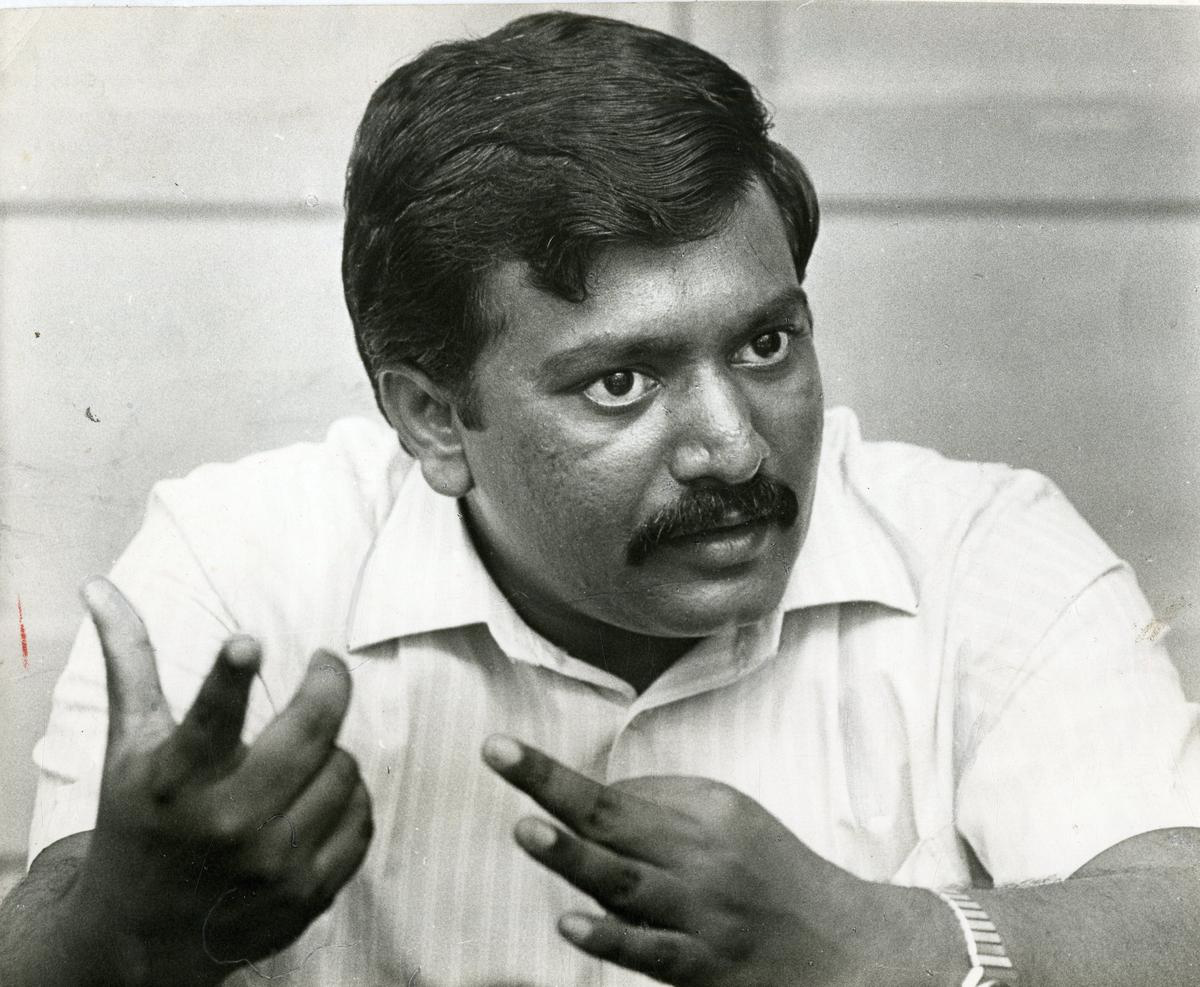

Author – Rathindra Kuruwita is an Associate Fellow at SAFN. He is a journalist and a researcher from Colombo, Sri Lanka. He holds a MSc in Strategic Studies from S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, Singapore. He was also a fellow at Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, USA, and a participant of the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) conducted by the U.S. Department of State. He writes on security and international relations to several publications and has written extensively on the Sri Lanka-China relationship.