By Md Salman Rahman

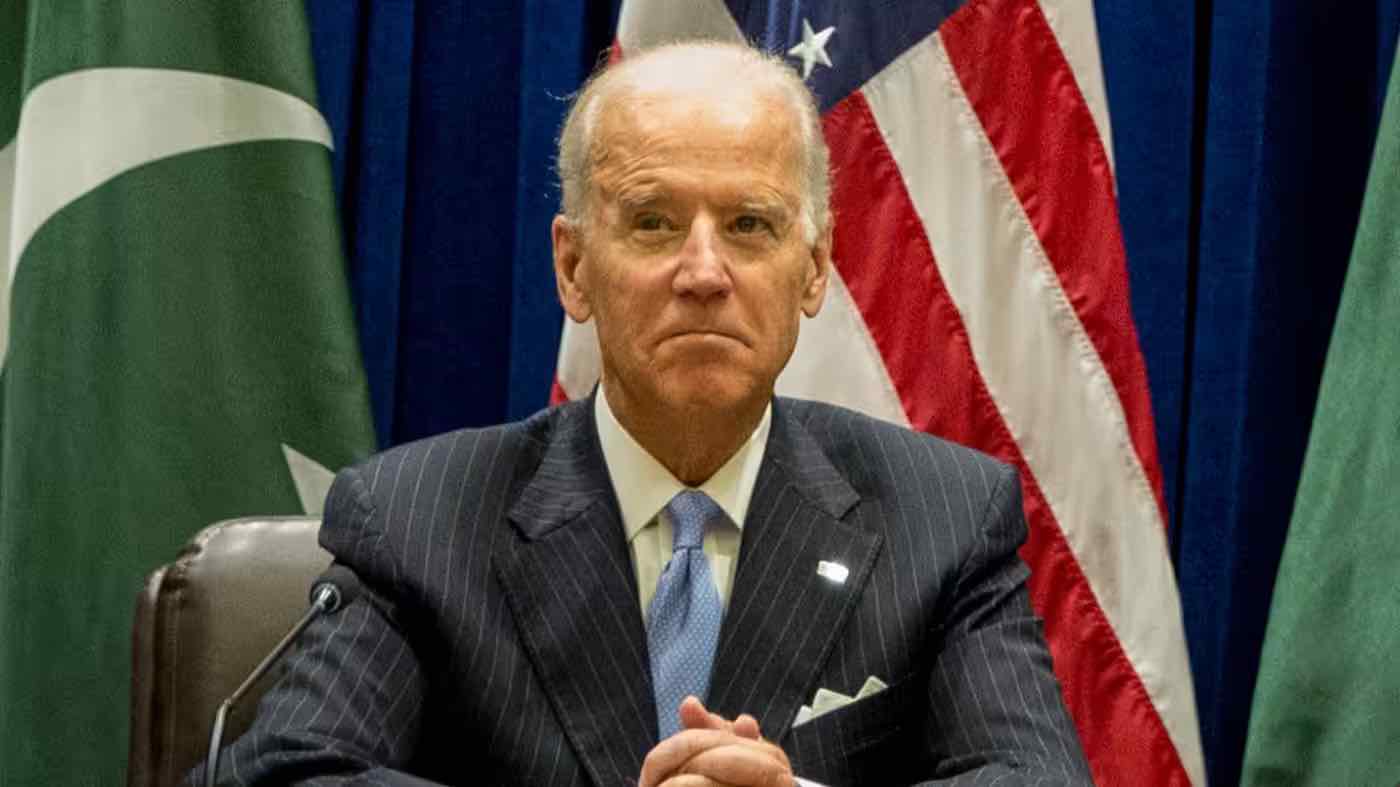

Given its security and strategic issues, the US was too reliant to question Pakistan’s democracy and the involvement of the military in undermining its democratic backbone.

Despite being shot, sentenced to jail, and banned from all political activities in his country, Imran Khan remains a prominent figure in shaping Pakistan’s political discourse. On February 8, a widely debated nationwide election occurred, with the military regime alleged to have played a covert role in the process. In light of clear evidence of election rigging and harassment of opponents, the West, especially the United States, which claims itself as the guardian of democracy, has yet to put any diplomatic pressure, let alone harsh measures Washington took in recent years for Bangladesh, Nigeria, Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, including visa restrictions and asset freeze. Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Centre, said U.S. State Department statements were “relatively mild … considering the great scale of the rigging that went down.”

“United States, which claims itself as the guardian of democracy, has yet to put any diplomatic pressure, let alone harsh measures Washington took in recent years for Bangladesh, Nigeria, Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, including visa restrictions and asset freeze.“

When asked about Washington’s take on the election rigging and the military’s complicit role in violating the democratic process, White House spokesperson Mathew Miller said it was a “Pakistani process led by Pakistanis,” adding that was “not a party to it.” Even as the White House knows this power transition has failed to mirror the people’s will, the question remains why does Washington maintain a double standard as to Pakistan’s democracy?

These answers lie in various aspects.

Firstly, driven by strategic interests the United States has historically aligned itself with Pakistan’s military regime, from Ayub Khan to Pervez Musharraf. The alliance was solidified during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, when Pakistan’s support was instrumental in countering communist forces. Later on, in 2003, during America’s invasion of Afghanistan, Pakistan’s cooperation was pivotal in the “War on Terror,” along with the pursuit of capturing Taliban leaders once backed by Washington. In today’s era of multifaceted conflicts and the rise of China as a strategic rival in the Indo-Pacific, Washington’s focus shifts from moral concerns to strategic pragmatism, underscoring the necessity of balancing relations with Islamabad across many fronts.

“it is undeniable that, at the very least, Pakistan granted airspace for America to conduct the strike.”

Secondly, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan began a fresh start for a new era in South Asia’s politics. The Taliban as victorious is in power, erupting the threat of returning Afghanistan to a safe harbour of terrorism. Just less than one year after the withdrawal, Al-Qaeda leader Ayman- al-Zawahiri was killed in a US drone strike at the heart of Kabul. While Pakistan denied involvement in the strike, Taliban leaders accused Islamabad of aiding Washington by providing information about Zawahiri’s whereabouts. Regardless of the veracity of these claims, it is undeniable that, at the very least, Pakistan granted airspace for America to conduct the strike. This underscores Washington’s recognition that, to prevent a recurrence of the 9/11 attacks, the US requires Pakistan, particularly by leveraging its formidable military.

Furthermore, in recent years, Pakistan and Afghanistan have not been sitting well in terms of many issues, including the Durand Line disputes, and the resurgence of the attack on Tehreek-E-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), motivated by the Afghan Taliban. Former Pakistani Caretaker Government Anwar ul-Haq Kakar, who was believed to be close to Pakistan’s military, accused, “in a few instances” there was “clear evidence of [the Taliban] enabling terrorism” by the TTP. In addition, the controversial decision to expel 1.7 million undocumented Afghan refugees from Pakistan was a result of the strained relationship between Islamabad and Kabul. Many right-wing politicians, including Mr Kakar, believed this was meant to put pressure on the Taliban. This signals that there is no way soon regarding close ties between the Taliban and the Pakistani government; rather, a fair chance persists, that the strife relationship may deteriorate in the foreseeable future, which in many ways serves Washington’s existential interest to curb the influence of the Taliban administration.

“Amidst the backdrop of Islamic and Western tensions, this development prompts speculation on whether Pakistan’s military could emerge as a viable tool to exert pressure on the Iranian regime that may yield strategic outcomes for Washinton.”

Thirdly, Iran has been the US’s top concern regarding its strategic interest in West Asia. Washington and its allies have been leaving no stone unturned in containing Tehran and its proxies’s aggression in the region. On January 16th of this year, Iran carried out missile strikes in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, targeting the hideout of the anti-Iran insurgent group Jaish-Al-Adle (Army of Justice). As expected, within two days, Pakistan’s military responded not only with missiles but also deployed fighter jets in Iran’s Sistan-Baluchistan province, citing the presence of anti-Pakistan ethno-nationalist insurgent groups. Amidst the backdrop of Islamic and Western tensions, this development prompts speculation on whether Pakistan’s military could emerge as a viable tool to exert pressure on the Iranian regime that may yield strategic outcomes for Washinton.

Fourth, Pakistan’s arch-rival, India’s strategically ambivalent paramour caught between its historical flame with Russia and the allure of a new romance with the United States in the competition with China. Since Russia’s brutal war on Ukraine, India sided with Russia as it refrained from directly condemning Putin’s aggression and has continued to purchase Russian oil which eventually strengthened Moscow to avert Western’s economic sanctions. America is not happy with India’s ambivalent stance but can’t at the same time put pressure, fearing it may push Delhi closer to Moscow. This predicament presents Washington with a challenge, leading the White House to maintain a careful balance in its dealings with Pakistan, even if it becomes undemocratic, so India may not consider itself indispensable in South Asia’s Politics.

Fifth, Washington has been comfortable with Pakistan’s military-backed government, realizing it may be easier to manipulate a government that lacks legitimacy and does not reflect the will of the people. When Mr. Khan expressed dissatisfaction with American interests, he was swiftly ousted from politics, with his party suspecting US involvement in collusion with the Pakistani military. The aftermath is well known. This incident echoes a historical pattern, exemplified by the house arrest of Pakistan’s nuclear pioneer, Abdul Qadir Khan, at the request of the White House to prevent the scientist from sharing sensitive information with Washington’s adversaries like North Korea, Libya, and Iran. If it is way easier to manipulate the army or an army-backed weak government, what is the use of demanding democracy in Pakistan?

“Pakistan is in dire straits, not only politically but also economically.”

Pakistan is in dire straits, not only politically but also economically. Inflation is now 33 percent. The government almost survived the default in June 2023 with a $3 billion bailout package from the IMF. Despite critics’ assertions that the payroll of nearly one million military personnel significantly impacts government expenditure, the military continues to claim itself as a ‘safeguard’ against potential threats from India and remains a crucial security bulwark in the region.

Given its security and strategic issues, the US was too reliant to question Pakistan’s democracy and the involvement of the military in undermining its democratic backbone. Rather, from 2002 to 2010, $19 billion in aid from Washington flowed to Islamabad with a $2 billion average for counter-terrorism. Most of the aid was invested for security purposes, which merely strengthened the Military’s strength neglecting civilian and development initiatives. Experts believe that with the help of such aid, this powerful military has become more powerful today. Yet, the coin has its flipping part too.

The swift rise in youth support for Khan presents a challenge for the US in managing its relationship with Pakistan’s military and undemocratic institutions, given that youth constitute a significant portion of the electorate, with 56.86 million out of total voters of 128.58 million. With Khan’s party securing a decisive majority in the latest election, there’s a potential for a surge in democratic values. Now is the moment for America to reassess its moral compass, which has been dormant for decades; it’s time to reshape and uphold its moral dimension, which could ultimately serve its strategic interests in South Asia.

But if the White House fails to change its conventional stance towards Pakistan’s democracy, there’s a risk of growing anti-US sentiment among the youth, which may not only strain future US-Pakistan relations but may cast doubt on America’s legitimacy being the champion of Democracy around the world.

Md Salman Rahman is a Research Assistant at South Asia Foresight Network (SAFN) from Bangladesh